Amid the global uprising against anti-Black state violence, we put together a short newsletter to send to our comrades inside who live on the front lines of this struggle. It can be printed on 3 sheets of paper, so it can be mailed with one US stamp. We hope it’s useful. Below the file is the text of the letter.

DEAR COMRADES,

Across the stolen land currently occupied by the United States, people are rising up, taking the streets, and demanding an end to state violence. The incident that sparked this was a familiar one: A Black man, named George Floyd, was murdered by the police in Minneapolis. You’ve probably seen the horrific footage of a fascist cop named Chauvin suffocating the man known and loved as “Big Floyd” by kneeling on his throat for 9 minutes. But it’s also clear that while people are honoring the memory of George Floyd, they are not just fighting back against this one instance. In the streets, people are shouting and singing the names of others killed by police. Some of them are names so many people know: Michael Brown. Sandra Bland. Eric Garner. Akai Gurley. Oscar Grant. Tamir Rice. Philando Castile. Trayvon Martin. Layleen Polanco Xtrava- ganza. And some names are new.

SAY THEIR NAMES

Tony McDade, a Black trans man, was murdered by police in Tallahassee last week. The name of the cop who killed Tony is still unknown, protected by a Florida law that allows cops to be classified as victims in order to preserve their anonymity. Tony went by the nickname “Tony the Tiger” and is remembered by his friends and family for his big heart and uplifting energy.

Breonna Taylor, a Black woman was ambushed in her home and killed by cops in Louisville shortly after midnight on March 13th. Police used a “no knock” warrant to break in with no an- nouncement–which was granted without question by a Louisville judge–while Breonna and her boyfriend were sleeping. Breonna was 26 years old and known for her immense adoration for her family and friends. She was an EMT working on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic with plans to become a nurse.

Nina Pop, a Black trans woman was murdered in her apartment in Sikeston, Missouri on May 3rd. Nina Pop is at least the 10th trans person to be murdered this year in the US. Black trans women are the single most criminalized group of people in the US–almost 50% of Black trans women will be locked up at some point in their lives. We know that what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “organized abandonment” goes hand in hand with direct state violence, and violence against Black and trans people is closely tied to the prison system whether it’s carried out by police or not. Rest in power, Nina!

Ahmaud Arbery, a 25 year old Black man, was killed by non-police white supremacists in Geor- gia on February 23rd. Only after more than a month of outrage and organizing were charges brought against the murderers in this lynching. The killers were father and son and avid Trump supporters.

James Scurlock, a 22-year old Black man, was murdered on May 30th while protesting in Oma- ha, Nebraska. A white supremacist bar owner, who was screaming the n-word at protesters, started waving a gun around. Scurlock tried to disarm him to protect the crowd and was shot twice in the process. Prosecutors will not bring any charges against the white supremacist property owner.

David McAtee was killed by police in Louisville. He is fondly remembered as a generous mem- ber of the Louisville community who made some amazing food at his restaurant YaYa’s BBQ, which was named after McAtee whose nickname was YaYa. He frequently served people in need for free, and even served cops for free. They murdered him.

Malik Tyquan Graves. was killed by a hail of at least 19 shots from 10 cops. The news immedi- ately reported him as dangerous and criminal to excuse the police murder. But Malik’s death was not caused by Malik or any of his actions.

Jamel Floyd, a 35-year old Black man, was killed in his cell at the Metropolitan Detention Cen- ter in NYC this week. CO’s maced Floyd in his cell, knowing that he had asthma, and left him to die. Floyd’s family had been looking forward to reuniting with him soon, because he was going to be eligible for parole in October 2020.

George Floyd was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25th. He was the father of two young daughters who worked security at a local restaurant to provide for his family. Friends and loved ones knew him as a guy who had your back no matter what and who always looked for ways to be a better father and community member. His sister remembers him as a “gentle giant.” Floyd pleaded for his life for nearly 9 minutes while Chauvin actively suffocated him. His last words, like Eric Garner’s, were the haunting and now all too familiar “I can’t breathe.”

UPRISING & SOLIDARITY EVERYWHERE

It has now been over two weeks since the first night Minneapolis erupted in protest. Despite curfews being established and violently enforced in towns and cities across the country, the fire continues to spread. Actual fire: Minneapolis protesters seized and burned a police precinct to the ground, and liberated some goods from a Target, redistributing them to the people. Mixed tactics have been used, with the usual hand-wringing about the need for “peaceful pro- tests.” Reformers often demand that Black people be peaceful even as they are being attacked on the daily by police. But peace and submission are not the same. Peace is what the people are fighting for, but that doesn’t mean it’s what they fight with.

Thousands are marching through the streets of London, where the city’s Black Lives Matter organizers expect upcoming protests to be the movement’s largest yet in the UK. On Tuesday June 2nd, tens of thousands filled the streets of Paris in solidarity with Black people in the US and against police violence. Ultimately protests have erupted on 6 continents, with actions in Nigeria, Kenya, Japan, Brazil, Australia, and across Europe.

A mural of George Floyd has been painted on a border wall in occupied Palestine. The move- ment is international, and growing daily. As repression in the US grows more violent and more militarized every day, National Guard units, private security forces, riot-trained COs, and even TSA employees have been called in to crush the insurgency. So far, it’s only growing.

Minneapolis: In Minneapolis, the demonstrations have resulted in a police precinct being burnt down and an entire city being halted and seized by protests for days on end. But they have also been building: an empty hotel was taken over to house people in need of shelter. A people’s town hall was held where the mayor was given a chance to publicly announce a plan to defund the police. He refused, and was booed and shamed. Minneapolis city council even voted to dis- band the city police department. There remain serious questions about whether they have the power to do so–legally, politically, and socially. But the powerful fact remains that what is pos- sible, right now, is fundamentally changing from what was possible a month ago. The young Black leaders in Minneapolis have accomplished more in 2 weeks than non-profit reformers could manage in half a century. They have shown once again that the power is with the people. .

NYC: For days, thousands of people have participated in dozens of marches and protests across New York City. NYPD has responded with typical violent repression. They have beaten, pep- per sprayed, and tear gassed protestors. They have run protestors over with SUVs. They have blocked protestors from the subway before curfew to arrest them for breaking curfew. Over the scanners, we have heard them advise each other to “run them over” and “shoot the MFers.” Meanwhile, the liberal mayor of NYC, Bill de Blasio, has said “an attack on police is an attack on all of us.” Meanwhile his police brutalize protestors, especially in the Bronx.

TWU Local 100, the NYC public transit workers’ union, refused to help police transport their detainees in a massive show of solidarity. The announcement came after one brave bus driver stepped down from his bus and said “No” to the NYPD. Rank and file union members like this one are the ones with the real power. He and others like him forced the TWU to take this posi- tion–even though union bureaucrats have been supporting adding hundreds of new salaried police to harass teenagers and homeless people in NYC subways over $2.75 fares.

Louisville: At the time we’re writing this, Louisville protesters have been out 13 straight nights, often in rain and usually under violent repression from police. They are fighting for their neigh- bor Breonna Taylor, and for Black people living under police occupation everywhere. The police department has been combative and defiant of the liberal mayor, who seems to be unable to control them.

Chicago: Thousands more filled the streets from downtown to some of the suburbs. On May 31 mayor Lori Lightfoot ordered police to corral protesters in the Loop by closing bridges and shutting down the city’s entire public transit system. Cops attacked the cornered protestors. While arrests surged, the Chicago Community Bail Fund was flooded with so many donations that the website crashed. When Chicago Public Schools temporarily suspended its free meals for kids, people pulled together to make and deliver those meals.

Philly went off too: Thousands and thousands of people took the streets over the weekend of May 30 and into the week. A video has circulated of police trapping hundreds of people against an abutment and tear gassing them. Late at night on June 2, the racist statue of white suprem- acist mayor Rizzo was removed after being repeatedly defaced and targeted by protestors.

A MOMENT FULL OF UNCERTAINTY AND POTENTIAL

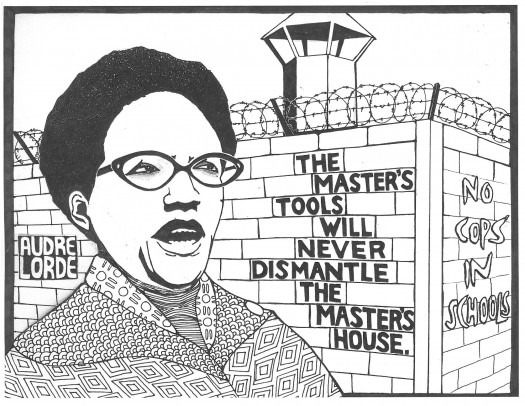

What’s most amazing about this uprising is the scale and the political messages that are cir- culating. Small, tiny, rural towns across the country are having anti-police protests! People are shouting “Black Lives Matter” in places where that would have been unthinkable 5 years ago. And more and more, abolitionist demands are gaining popularity. On top of the reformist de- mand to incarcerate the cops who kill people, we are hearing calls for defunding the police, abolishing police, and the slogan “Free Them All” is front and center. Political consciousness is higher right now than it has been in a long time in the US.

At a moment when the two-party electoral system has shown once again that it exists to pro- tect the existing order of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism, people are making their own demands and exploring new methods for doing politics. Joe Biden’s most substantive contribution to the problem of police violence has been to suggest that police are trained to shoot people in the leg instead of in the heart, reminiscent of the Israeli Defense Force Policy towards Palestinians in Gaza during the Great March of Return in 2018. Trump has been hiding in his bunker, except for one strange photo op where he awkwardly held up a bible–and to do this, his goons tear gassed protesters to clear them out of the way. They are lost and scared–the power of the people is beautiful in comparison.

At every level, the US and capitalism are in deep crisis. Police legitimacy is evaporating by the hour. The federal government is a disorganized shambles. Millions are jobless, and a poorly managed pandemic continues to rack up preventable deaths. The veil of order is falling away, revealing the chaos of what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “organized abandonment” and violence of the carceral, punitive state that so many already know too well. The people have had enough.

During this frightening time, when there are so many to mourn and there is so much loss to hold, we are also optimistic. We are seeing a massive people’s uprising. And while the demon- strators don’t all have the answers, they are asking the right questions, and they are ready for a new world. As abolitionists, we should welcome this historic opportunity. We must deepen our connections, advance our political education, and stand strong together until we have the just world we know is possible. We know that you, as incarcerated people, live on the frontlines of the struggle for justice. And you are not forgotten.

NEWS FROM THE LOCKED DOWN FEDERAL PRISON SYSTEM

Peace to all my loved ones & comrades. As you may know, the BOP for the last week im- posed a lockdown within an already existing lockdown on all of its prisons nationwide. During the latest round of abuse, we all, everybody in mediums & maximums, were held in SHU-like conditions for 7 days. We were denied access to emails, phone calls, commissary and even showers. Two showers in 7 days, and that was only because peo- ple protested the conditions. I personally complained to one of the lieutenants initially, and he tauntingly replied that I should “wash my ass in the sink.” But that was how we were treated in what was another supposedly “non-punitive” lockdown, within another lockdown that has been imposed since April 1.

This latest one amounted to the BOP holding us hostage, to keep us disconnected from the righteous rebellions and demonstrations that were going on outside. Remember that wave of consciousness and solidarity often spreads from outside into the prison system, because a majority of us come from the most oppressed communities. Prison administrators know that more than 60% of the Prison Nation are potential George Floyds, Breonna Taylors, Sandra Blands & Eric Garners. That number gets higher, Black- er and Browner in the higher security facilities. We not only come from neighborhoods that are under police occupation, but we also, as incarcerated people, experience end- less, pervasive, state violence and surveillance — a stark illustration of this is that on the first day of this new lockdown a detainee in MDC Brooklyn was pepper sprayed to death, but that doesn’t make CNN and NPR. Therefore the struggle that’s going on outside is naturally and inseparably our struggle as well, and no lockdown can change that.

In Love and Struggle [Anonymous comrade]

A STATEMENT FROM OUR EDITOR, STEPHEN WILSON

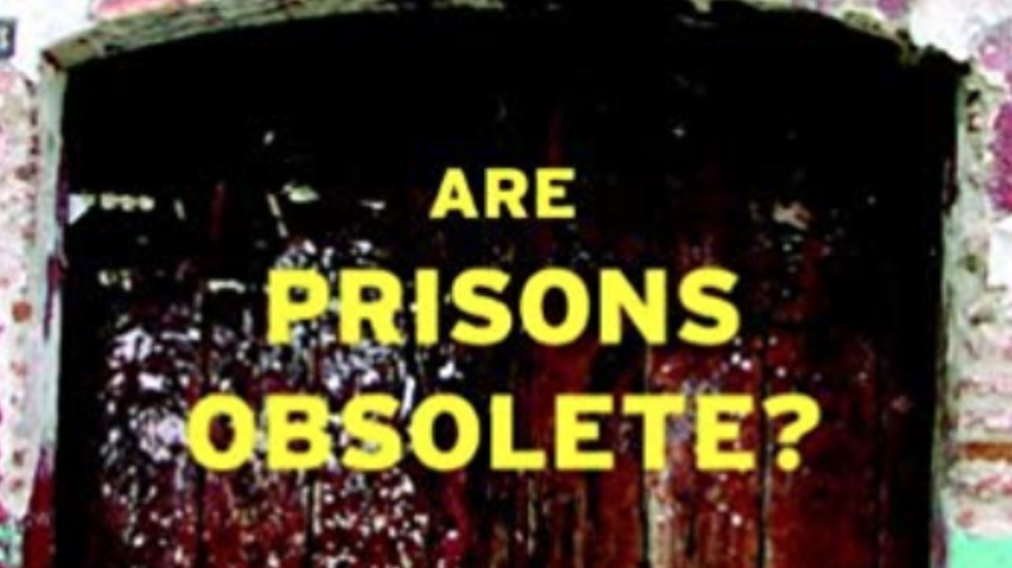

I want to stress that we must take this time to think about what we want instead of policing. People are upset, in a rage, and tearing shit up. But as abolitionists, we know that the real work is about building things up. Anyone can tear shit up. But how many can build something worthwhile and lasting? That is our task. We need to engage with folks and start talking about what we want instead of the cops. How can we make the police obsolete? What do we need to build in order to make them obsolete?

We need to go into communities and talk about what we, meaning the people in these communities, want. We should listen. The government isn’t. We understand the pain and frustration. But we have to make this moment a movement.

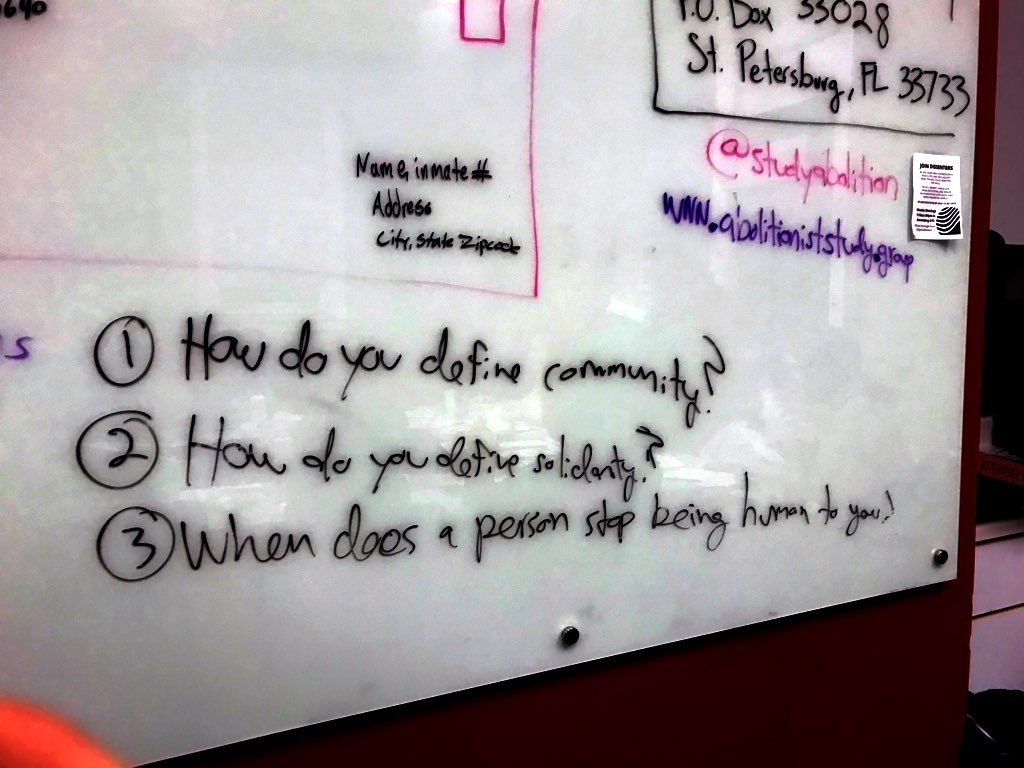

That means we have to work to build connections. Real safety is achieved through good relations. Relationships, good ones, make people feel safe. Let’s work to build relation- ships with people. Let’s listen and discover what is already there that we can build from. Let’s get connected. Let’s encourage people to connect with each other, to show up for one another. Let’s talk about how to solve conflict and address harms without the cops. Some of that is already happening. Let’s find out what those things are and amplify them.

This is our task. We must build. That’s what abolition is about: a presence, not just an absence.

Always, Stevie

IN THE BELLY // PO BOX 67 // ITHACA, NY 14851